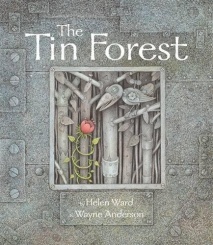

"There was once a wide, windswept place, near nowhere and close to forgotten that was filled with all the things that no one wanted." So begins Helen Ward's tale of the Tin Forest where an old man lives who tidies the rubbish and dreams of a better place. With faith, ingenuity and hard work, he transforms a junkyard into a wonderland in this poetic modern fable.

Publishers Weekly

"Living alone in the midst of environmental devastation, an old man refuses to resign himself to the junkyard views that surround him," wrote PW. "Exquisitely detailed illustrations endow this touching tale with pathos and grace." Ages 3-9. (Oct.) Copyright 2003 Reed Business Information.

Helen Ward sets her story in a garbage dump, "near nowhere and close to forgotten, filled with all the things nobody wanted." An old man lives here, obviously forgotten, too. Every day, he tries to clean up the place. Every night, he dreams of beautiful woods. But when he wakes, "the world outside [is] still the same." Then, one day, a shattered lamp reminds the old man of a flower—and, inspired, he begins sculpting the trash into a forest. "It was not the forest of his dreams," Ward admits, "but it was a forest, just the same." Complete with metalic myna birds, the "woods" are cheerful but colored like the night. "All day the old man walked through the silence, and his heart ached with emptiness"—until a moonlit wish makes real birds appear. They bring seeds, and soon a living forest, colored like the day, assimilates the metals with dynamic petals. The Tin Forest almost seems to be two books at once. Ward's lyric prose, by itself, would be a hopeful tale—but only cautiously so. Ward never explains why her protagonist is in the place he is in, why he does not (or cannot) leave, why he is without companionship, yet "surrounded by other people's garbage." Conversely, Wayne Anderson's gentle cartoons seem sweetly untroubled. He colors his "garbage" with various pastel-tinted grays. We see no recognizable things except the lamp: no ragged clothes, broken toys, or sagging sofas. Only metal parts can be identified: Pipes, wires, and cogs lie in piles. Pebbles and odd-shaped bits dust the ground. Mixing perspectives on a page creates a jumbled look, but homogenous color makes the garbage look quite clean. The monochromatic palette later gives spreads of the man-made forest a "hidden picture"quality. Young readers will enjoy searching among the pipes and bolts for the figures the old man made: tin lizards, tigers with wire whiskers and flathead screws for eyes. As time passes and living animals appear, the screwed-in eyes cleverly "open" when the screws fall out, leaving a circle of sight. Ward closes her story in "a forest, near nowhere and close to forgotten, that was filled with all the things that everyone wanted." The words match the mood of the illustrations most closely, yet also seem, somehow, untrue. The unnamed, unseen "everyone" is the same lot who left the old man to sort out their garbage. How could they possibly be wise enough to appreciate the vision of "an old man who never stopped dreaming"? 2001, Dutton, 36 pages,

— Diana Star Helmer

Children's Literature

A lonely old man, living in a small house amid a trash-strewn "wide, windswept place, near nowhere and close to forgotten," dreams of living in a colorful forest filled with animals, birds and flowers. One day, inspired by a broken, flower-like light fixture, he stops trying to clean up and begins to build a forest from the scrap around him. Magically, as it grows, he is joined by birds, which drop flower seeds, finally ending as his dream comes true. This thought-provoking tale is simply told in poetic prose that encourages Anderson to create a surreal world, but one that enhances the message of a possible brighter future. The sensitively designed single and double pages of the visual narrative juxtapose the mechanical and the organic, presented on the cut-out jacket and cover as a mechanical forest in shades of gray challenged by a spiraling green vine and red flower. The grainy textures of the finely detailed illustrations soften the tints of color, making each scene an emotionally involving tableau; an inspiration for our troubled times. 2001, Dutton Children's Books/Penguin Putnam Books for Young Readers, $15.99. Ages 4 to 9. Reviewer: Ken Marantz and Sylvia Marantz

School Library Journal

Gr 1-3-A tale with a pointed ecological message. Ward begins pessimistically with the words, "There was once a wide, windswept place, near nowhere and close to forgotten, that was filled with all the things that no one wanted." In the midst of this forlorn environment, there lives an old man who remembers better times and dreams of beautiful forests teeming with exotic birds and wildlife. Even though he tries to clear away the trash, his world remains essentially the same. One day, he plants a light bulb that takes root and grows and grows until it creates a forest made of tin and garbage. Two birds drop seeds on the dry ground; they sprout and bloom, bringing insects and small creatures to the land. The last page reiterates the first with this change: "There was once a forest, near nowhere and close to forgotten, that was filled with all the things that everyone wanted." Anderson's sinister illustrations emphasize the gray coldness of the tin forest. Colors are added as the new one comes to life. The pictures are reminiscent of those in early German folktales, depicting the forest as dark and deadly. With true eloquence, Ward has created a morality tale of environmental devastation. A good choice for Earth Day collections.-Barbara Buckley, Rockville Centre Public Library, NY Copyright 2001 Cahners Business Information.

Kirkus Reviews

In this parable from Ward (The Animals' Christmas Carol, above, etc.), an old man living in a vast, gray wasteland of "other people's garbage and bad weather" is driven by dreams to recycle it all into a forest of steel trees and tin creatures. Soon, however, a real bird comes, then another, and before long a living forest is flitting and twining itself through the metal framework. Anderson faithfully portrays every leaf and vine, every nick and rivet, coloring the junk in dingy blues, living creatures in brighter hues. Brief, large-type text in a soft gray mimics the drab forest at first and echoes the heart of it once the colors have taken over. Less developed both in art and storyline than Colin Thompson's similarly themed Paper Bag Prince (1992), this may still furnish thoughtful readers with indirect motivation to act on their hearts' desires. Libraries may be forced to discard the dust jacket, which has a big die-cut hole in the front. (Picture book. 6-8)